On Wikipedia, there’s a sarcastic take on the re-discovery of the Zanja Madre, the original water supply for the city of Los Angeles:

In 1978 archaeologist Julia Costello discovered a portion of the Zanja Madre during construction of the Plaza de Dolores.

In 2000 two people allegedly dug up a section of the Zanja on the steep slope near a Broadway parking garage and were credited by the L.A. Weekly and Los Angeles Times as having discovered the Zanja, but as it turned out later, they had merely come across the well-known brick “bulge” between the parking garage and the UP paint barn while trespassing on Union Pacific property. Later, archaeologists overseeing site operations near the MTA Blue Line, later named Gold Line, studied the portions of uncovered brick conduit. They expected to find more portions along the line near the River Yard, but there were no discoveries. It was generally supposed that the Zanja had been destroyed during railroad yard construction over the years. Another brick find, supposedly on private property, was uncovered during a weed whacking operation. Since it was private property, no archaeological surveys were made. This part of the Zanja was what was supposedly discovered in 2000. It is an area on the back side of an abandoned mill on Spring Street, and the old Union Pacific paint barn, which had been a favorite area for mill and UP employees taking their cigarette breaks. This area, which is open on the side facing Broadway in Chinatown, and from the Spring Street side, had been a playground for the local children and source of bricks for local gardners for many years. This is one reason why many locals met the news of the new “discovery” with puzzlement, for the location of the Zanja had been known by almost everyone living in Chinatown, Dogtown, Elysian Park, Solano and Echo Park.

In 2005 MTA construction crews uncovered unexpected sections of the brick Zanja Madre. This section was found following the path predicted by early Zanja investigator and amateur archaeologist, Rudy Zappa Martinez in 1975, when he used a compass and stick to follow the Zanja’s path from its terminus in Olvera Street, along to the bulging section behind the Union Pacific paint barn, up to the point where it disappeared into the sandy hillside by the cornfield trainyards, and onwards toward the river. Archaeologists were brought in to evaluate the finds, most of which were red-brick, penstock-sized aqueducts. Now serious studies and documentation have begun in order to have the Zanja Madre routes put onto historical registers.

Once again, the people’s history of L.A. trumps the official history. Archaeologists are always looking for cultural resources, but can neglect to talk to the “cultural resources” who have been living in the area for decades, and have local knowledge that never got written down because nobody thought it was worth recording. Anyway, I’ll get off the soapbox now.

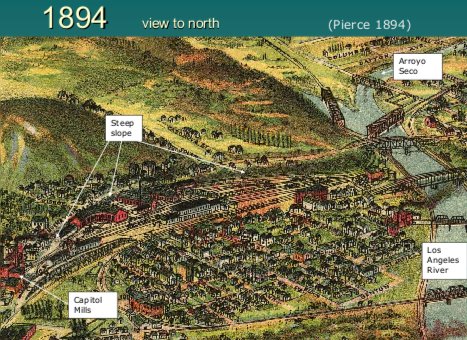

Built by the settlers of Los Angeles shortly after the city’s founding, the Zanja Madre was the main water supply for the city, a channel diverting water from the LA River to the Plaza that constituted downtown LA in the 1780s. The Zanja Madre was part of a larger water supply system of zanjas, or ditches, that stretched across the city, with 90 miles of channels. The zanjas were the city’s main water supply until 1902, when the system was replaced with underground pipes. After this conversion, the Zanja Madre remained in use as a system of flood water drainage.

Eastlake and Westlake, now known as Lincoln Park and Macarthur Park, were originally reservoirs for water flowing in the zanjas. When there was a dry spell, you could get water from these manmade lakes. (Yes, it sounds disgusting. Just forget the past 50 years of history around these parks.)

The two people who discovered the remains of the ditch were documented in The History and Archaeology of the Zanja Madre, a good Powerpoint deck produced by Cogstone, an archaology firm hired to research the Zanja Madre after MTA construction uncovered part of it in 2005. The illustration above was from that report, and they have numerous maps and photos of the zanja. They also have a video about the uncovering and archaeology.

Ultimately, the uncovered portions were entombed in concrete after research was conducted on the ruins.

More reading:

A history of water in L.A., provided by the City, has a short overview of early water systems.

Irrigation development by William Hammond Hall describes the local irrigation system, c. 1880, in detail.

Paralleling the sidewalk on the west side of Figueroa alongside the St. Vincent church parking lot there still exists a remnant of the channel that used to carry the water past homes there and along Adams Boulevard.

Nice topic!

James rojas took me to the zanja around 99′ to show me it, really got my juices going about getting into urban planning. A homeless guy was living partially in it back then.

I remember Zappa-Martinez scouring the train yards in the 70s, and his discovery of the main route of the Zanja at the time, being ignored by the authorities at the time. But years later, these same experts falling over themselves and giving credit to the newbie yuppies, who took credit for something that was never lost.